As human beings, we have an innate desire to gain a sense of control over our lives. We go to great lengths to control our emotions, our relationships, our environments, our thoughts, and so on. We crave predictability and we scorn unexpected change. Even that friendly neighborhood “free spirit” who probably popped into your head as an exception to this still abides by a desire to have control and predictability in their life. No matter how spontaneous and go-with-the-flow a person claims to be, we all find comfort in knowing what the day will bring and adhering to a routine; it is, for better or worse, human nature.

The unfortunate truth is that control is an illusion. The idea of “having it under control” is entirely our perception rather than an objective reality. The truth is that quite literally nothing in our lives is completely under our control; anything that can happen, can happen. And while this can be a very unnerving fact to come to terms with, it can help to develop an understanding of what control really is, where it comes from, and what it can lead to.

At its core, control is rooted in fear. Specifically, the desire to control the people, places, and things around us is often driven by fear of what will happen if we don’t have control over those things. We take on a sense of responsibility for what goes on around us in an attempt to manipulate relationships and outcomes. Sure, our behaviors often influence our outcomes, but to make the jump that a certain behavior will undoubtedly and assuredly result in a certain outcome is a recipe for disappointment. Unfortunately, life is often far more complicated than that. Take for instance Mary, the thirty-something marathon runner in my family who after years of regular exercise and strict nutritious dieting, developed a deadly type of Leukemia that almost took her life. If controlling behaviors inherently controlled outcomes, that simply would never have happened. Her regular strenuous exercise, stringent diet, and overall healthy practices could never have logically resulted in the development of her cancer, and yet there she was, lying in a hospital bed for months on end receiving stem cell transplants and wondering how this ever could have happened to her.

Control is also often related to ego. When we manipulate and engineer every facet of our lives, we often do so in order to reach an outcome that we “know” must be what’s best for us. We brush off any feedback and suggestion that perhaps there are other paths and we narrow our vision and hyper-focus on what we believe is “right” for us. Again, this ego is deeply rooted in fear. Fear that we will not be okay on any other path, fear that we will not survive on any other road. When we learn to trust ourselves and practice acceptance, we develop the confidence we need to know that we will survive any turn or twist that is thrown in our path.

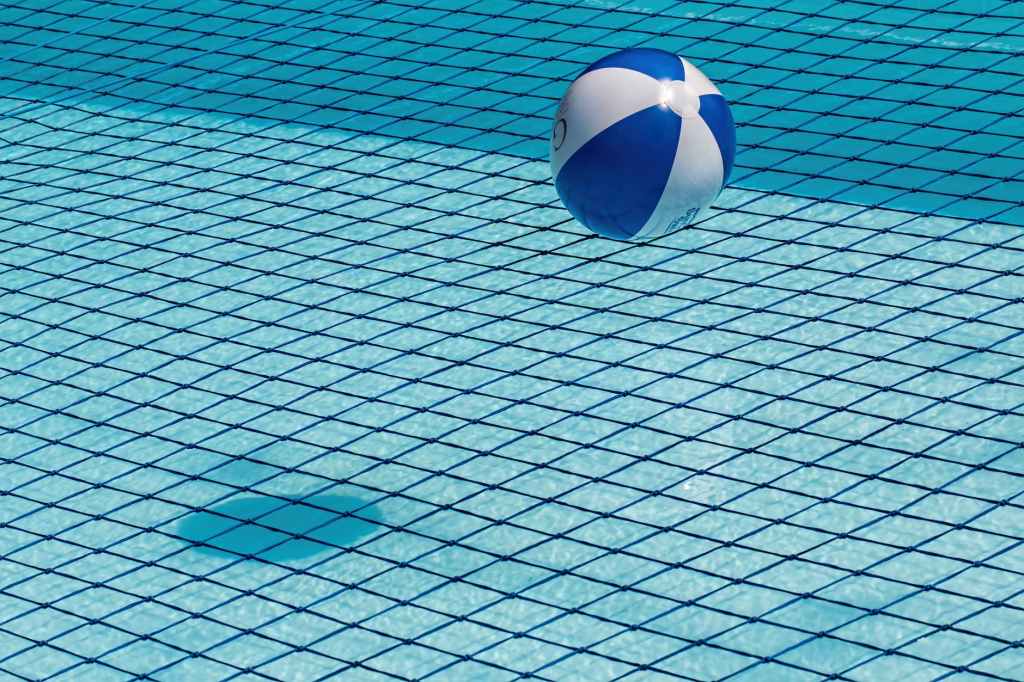

Finally, control can, and often does, lead to exhaustion. It is exhausting to micromanage your life and relationships. I liken this exhaustion to a common experience for children that grew up going to the beach as I did. I remember as a young girl on beach trips that I would go out into the water with a blow up beach ball and use all my might and all my strength to force the ball under the waves so that I could sit or even stand on it. There was something oddly fascinating about forcing that ball down, but every time without fail as soon as my grip slipped for even a second, up popped the ball. Attempting to control your life is like fighting with that beach ball. No matter how many times I pushed it beneath the surface, it always came back up. And what’s worse is that all that time and energy I spent fighting with that ball, I missed out on building sand castles with my cousins or snorkeling with my dad. By the time I gave up shoving the ball down, I was too exhausted to do those things even if I could have. Now I think back and imagine the things I could have done, the fun I could have had, if I had just let the ball float alongside me.

Ultimately surrender and acceptance are the antidote for compulsive control. That looks like me letting the ball float alongside me while I play in the waves. It looks like trusting the process and opening up to the possibility that maybe we don’t always have to know what’s best. It looks like Mary focusing all of her energy on healing and gratitude rather than on “where she went wrong.” It is not giving up. It is choosing to spend energy in a way that serves and benefits us. When we allow the inevitable cracks of life to happen to us without rushing to prevent them or fix them, we can truly let the light in.

***

This blog post was inspired by the tenets of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), an approach I use regularly in my work with individuals seeking solace from anxiety, depression, eating disorders, grief, and other difficulties. If you are interested in exploring these concepts further in your own journey, don’t hesitate to reach out!

Leave a comment